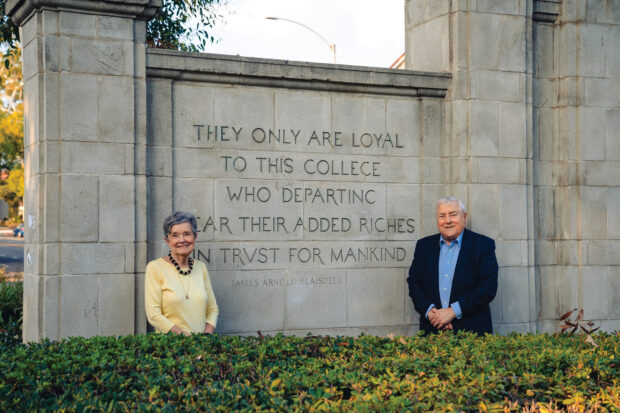

Going back more than seven decades, Pomona College first-years have been assigned a common book to read during the summer before they pass through the Gates, which they typically discuss in small groups moderated by a professor during orientation week. The idea is to give first-years something challenging and interesting to discuss with their classmates and to provide them with a taste of what college will be like. Sometimes the idea works. Sometimes not.

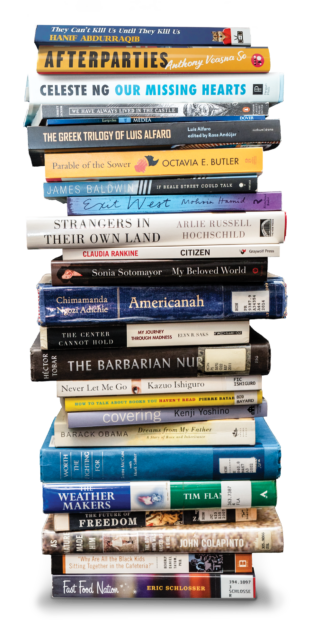

Among the variety of books selected over the last two decades are James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk (2019), Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s My Beloved World (2015), Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2011) and Fareed Zakaria’s The Future of Freedom (2006). An Orientation Book Committee composed of faculty, staff and students is responsible for each year’s selection. According to English Professor and committee member Kevin Dettmar, the team wanted to select a book that “modeled a critically sophisticated engagement with contemporary popular culture. Critical-thinking skills aren’t just useful for the classroom: they’re lifelong skills.”

This year’s selection was African-American poet and music critic Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (published in 2017), a collection of essays largely about music of the 1990s (much of it rap) and the artists who made that music. This year’s reading could not be more different than the reading assigned to my class in the fall of 1958, authored by social critic and essayist Lewis Mumford and titled The Human Prospect (published in 1955); that book was about almost everything under the sun except the music of the time.

This year’s selection was African-American poet and music critic Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (published in 2017), a collection of essays largely about music of the 1990s (much of it rap) and the artists who made that music. This year’s reading could not be more different than the reading assigned to my class in the fall of 1958, authored by social critic and essayist Lewis Mumford and titled The Human Prospect (published in 1955); that book was about almost everything under the sun except the music of the time.

About the only thing the two books have in common is that both are essay collections. Abdurraqib’s topics include “Chance the Rapper’s Golden Year,” “Death Becomes You: My Chemical Romance and the Ten Years of the Black Parade” and “The White Rapper Joke.” Mumford’s essays include such varied and unrelated topics as “The Monastery and the Clock,” “The Origins of the American Mind” and “Moby Dick.”

In 2024, literary critic Vincent Triola (author of numerous works of short fiction and a frequent book reviewer) described Abdurraqib’s collection of essays as “representing a generation’s lostness … caused by a technology-driven anti-intellectualism and superficiality that licenses poetry and authorship to anyone with a keyboard, inadvertently devaluing and obscuring quality literature.”

Abdurraqib’s essays are anything but superficial and anti-intellectual; they are well-crafted, beautifully written and, to use a word of the times, accessible, even for a reader now in his mid-80s. This year’s selection seems to have served as a good icebreaker for the racially, economically and geographically diverse Class of 2029.

Pomona is a very different place today from what it was in 1958. Three-quarters of Pomona’s Class of 1962 was from California (mostly from Southern California) with fewer than 3 percent students of color. By contrast, Pomona’s Class of 2029 is composed of students from 26 countries and 41 states (only 34 percent from California) and 55 percent students of color. If Abdurraqib’s set of essays was selected to prompt discussion across a diverse class, it was an inspired choice.

No one still alive remembers why The Human Prospect was selected. Perhaps Steve Pauley ’62 is correct when he muses that Mumford’s book was “assigned to terrify freshmen, most of whom were stars in high school. I guess the faculty wanted to drive some humility into us. What was terrifying was that at least some understood the book—at least they bluffed enough to pull that off.”

In contrast to Abdurraqib’s writing style, Mumford’s was anything but accessible. The book was tough sledding for children of the 1950s and hardly seemed designed to capture the interest of the 17- and 18-year-olds of the time. Gerry Wick ’62, a Ph.D in nuclear physics and now a Zen Buddhist master and author, recalls that he found Mumford’s writing style “turgid, arcane and too erudite to make for enjoyable reading.” Retired schoolteacher Bonnie Bennett Home ’62 remembers: “My professor was so disappointed in the election of The Human Prospect that he declined to discuss the assigned reading.”

Not every classmate of mine found Mumford’s book disappointing. John Roth ’62, a retired philosophy professor at Claremont McKenna, said that “our 18-year-old critiques of Mumford don’t cut much ice with me, nor do our 80-year-old condemnations. We should all hope to leave as much of a mark on our times as Mumford did on his.” Roth was enlightened by the essay “The Monastery and the Clock,” as “it opened my eyes as to how relatively recent the measurement of time is.” I, too, particularly liked that essay, and have often thought about its importance over the years. The remainder of Mumford’s essays, not so much.

Olhovskyi

Returning to the present, the selection committee spoke passionately about They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us.

“This book paints an image of the U.S. that is often shown differently overseas,” said Hlib Olhovskyi ’27. “Among a diverse list of excellent books, this collection stood out the most

for its captivating fusion of scope and detail, intimacy

and universality.”

Dorado

Zoe Dorado ’27 agreed. “[Abdurraqib] writes with a specific obsession that seems fueled by both love and uncertainty about the world,” she said. “He’s not an optimist, yet his work has a propelling force. It’s the type of book that I know I’ll return to during different stages of my life.”

“As I prepared to leave for college and reckoned with a desire for the relationships, places, and moments in time that I felt were disappearing, the appearance of Abdurraqib’s work in my life felt serendipitous and necessary,” said Nadia Hsu ’27. “Everything I’ve ever written since then has been kind of an imitation of Abdurraqib, and the way under his observation everything becomes sacred.”

Hsu

One can only speculate how the Class of 2029 will see the book with the perspective of 67 years. All that really matters, however, is how they regarded it this summer. Did it pique an interest in things unknown and spur lively discussion? Let it be said for now that in the view of this octogenarian, who found much of the book shocking but exciting, the Orientation Book Committee did its job well this year.

Mr. Eckstein ’62 is a longtime trustee of Pomona College, the parent of Timothy Eckstein ’92 and grandparent of Owen Eckstein ’28.