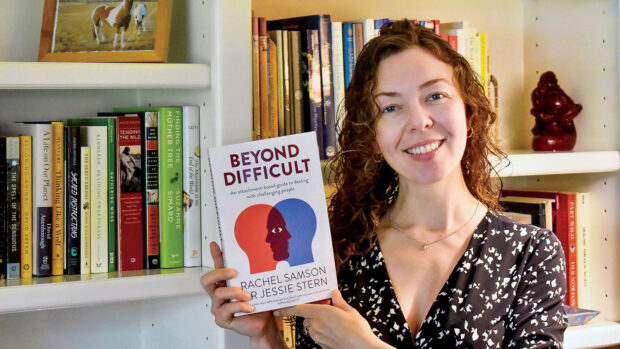

Last summer Assistant Professor of Psychological Science Jessica Stern ’12 published Beyond Difficult: An attachment-based guide to dealing with challenging people. An expert in attachment theory, close relationships and child development, Stern spoke with PCM about how she hopes the book will help readers.

Last summer Assistant Professor of Psychological Science Jessica Stern ’12 published Beyond Difficult: An attachment-based guide to dealing with challenging people. An expert in attachment theory, close relationships and child development, Stern spoke with PCM about how she hopes the book will help readers.

Who is this book for?

It’s for anybody who has had a difficult relationship—whether that’s in your family life, dealing with a difficult kid as an educator or as a parent, or navigating difficult work relationships. Most [of us] have had at least one relationship where we wished we had a guide we could pull out and say, “What do I do?” We wanted the book to be accessible, even to people who had never read a research paper before. We wanted them to know that there’s a fascinating science of how to build stronger marriages, friendships and workplace relationships.

You spend a lot of time focusing on highly sensitive and neurodivergent people. Why do you highlight these two groups?

These groups are often misunderstood and mislabeled, either as a bad kid or as a difficult adult. Everybody’s nervous system is wired a little bit differently [and] is not something we can change. But what we can do is provide a supportive environment that doesn’t overstimulate these kids so that they either act out or shut down. The same principle is true for adults—understanding that the person next to you might be more reactive to the context that they happen to be, we might look at the environmental circumstances that [lead] them to act in this way.

We also look at people’s relationship histories and attachment style. One major reason behind difficult behavior is that someone is feeling threatened, insecure or triggered. Usually that comes from a place of not having had secure, safe relationships as a child or as an adult. One nice thing about that framework is, first, it inspires a little bit more compassion, rather than combativeness, toward the person. But second, there are certain strategies that we can then use to help the relationship feel safe enough that the person can calm down and have a constructive conversation.

Secure vs. Insecure Attachment Styles

- Secure Attachment: Comfortable with intimacy and independence. Trusts partners.

- Anxious Attachment: craves closeness but fears abandonment, may appear clingy

- Avoidant Attachment: Values independence over intimacy. May appear distant.

- Disorganized Attachment: Desires connection but fears it. Sends mixed signals.

How did you and your co-author team up for this book?

Rachel [Samson] is a clinical psychologist in Australia. She and I met at a professional training many years ago and discovered that we had similar interests, but I was doing more of the scientific work and she was putting those ideas into practice with clients. It’s very easy for me, as a researcher, to say, “Here’s what people should do” in theory, but it’s a very different thing to be a practitioner who’s seen it in action with real people.

The book is divided into three parts. The first part is about understanding difficult behavior: getting a better grasp of what’s really going on when someone rubs you the wrong way. The second part is about working on oneself. Based on your own temperament and attachment style, what are the things that you’re bringing to this interaction that you can strengthen or improve? Part three is about the relationship. How do you strengthen it? What are specific things that you can do, like giving feedback in an effective way, not letting things stew? And what do you do when another person is just not going to change?