The year was 1925, and Pomona College had a problem: too many students wanted to enroll. The solution it kick-started a century ago this fall set the stage for The Claremont Colleges, an educational system unmatched in American higher education—and it all began with then-President James Blaisdell’s audacious idea.

In the “roaring ’20s,” Southern California’s population was exploding. Within a 60-mile radius of Claremont, the population doubled in just six years. The attractiveness of Pomona was so strong that by 1926, only one in four applicants gained admission. Clearly, the college needed to expand. But how to do so without becoming, as 1907 alumnus and Rhodes Scholar E.H. Kennard warned in a 1925 article in The Pomona College Quarterly Magazine, “one more drab university”?

In Oxford, a university eight centuries older than Pomona, President Blaisdell saw a possible model for the future: a collection of small colleges that share some common facilities while each maintains its own independence and identity. “I should hope to preserve the inestimable personal values of the small college while securing the facilities of the great university,” he wrote.

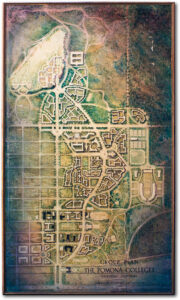

By 1925, what became known as the Group Plan was quickly taking shape in the minds of Blaisdell and other leaders—some of whose names are now etched in stone across campus. Among them were George Marston, Ellen Browning Scripps and William L. Honnold. In March 1925 Blaisdell gave a trustee-appointed committee his summary of the Group Plan. His right-hand man, Robert J. Bernard, took an all-night train to Sacramento to file articles of incorporation for the new educational enterprise on October 14, 1925, exactly 38 years to the day after Pomona itself was incorporated.

The new entity, says Brenda Barham Hill, who served as CEO of The Claremont Colleges consortium from 2000 to 2006, had three main functions. It would provide common services, hold land on behalf of the group and offer graduate education.

With tuition set at $150 per semester and seminars offered in 14 fields, including geology, Latin, psychology and zoology, classes began in 1926 at the clunkily named Graduate School of Claremont Colleges, known since 2000 as Claremont Graduate University (CGU). That same year the inaugural class of first-years was admitted to a new Claremont college named after Scripps, a philanthropist and supporter of education and women’s rights whose fortune was tied to the E.W. Scripps newspaper publishing empire. An ardent advocate of Blaisdell’s vision, she made multiple real estate purchases that became a significant part of the footprint for Scripps, CGU and three additional new colleges.

The end of World War II saw a flood of returning GIs ready to continue their education, and The Claremont Colleges were poised to admit them. The next 20 years saw the launch of three more colleges, including Claremont Men’s College (1946, later renamed Claremont McKenna College), Harvey Mudd (1957) and Pitzer (1963).

Thanks to Ms. Scripps’ foresight and real estate prowess, the colleges are almost entirely contiguous, minus Keck Graduate Institute located west of Indian Hill Boulevard. One easily walkable square mile—these days often biked, scootered or skateboarded—is now home to roughly 9,000 students, 3,000 faculty and staff, and nearly 3.2 million square feet of building space. The central library is the third largest among private institutions in California, behind only Stanford and USC.

Blending the vision and needs of seven distinct institutions that are at once partners and competitors has required informal collaboration and formal agreements hammered out over many decades. Sharing services, from an early steam-heating plant to sophisticated modern cloud-computing clusters, has occasionally required challenging negotiation and a recognition of the importance of “group over the individual.” As Blaisdell put it, “The whole project depends upon whether the participants are primarily interested in their separate organizations or, first of all, concerned in the creation at Claremont of a common and efficient center….”

And yet, a century in, the experiment shoulders on. The consortium has been modified over the years: graduate education, once the purview of all the colleges, is now housed in two distinct consortium members, and individual schools can choose to participate in some shared services but not others, with procedural guidelines and formulas in place to promote fairness. “Part of the genius of the model from day one was that they saw the benefit of sharing, and that it’s not static,” says Barham Hill.

Blaisdell would no doubt marvel at how his idea has flourished in what’s now called the “City of Trees and Ph.D.s.” When he became Pomona’s president in 1910, Claremont had no paved streets and Marston Quad was still a rye field. Now the colleges have collectively graduated about 100,000 alumni, and all five of the colleges are among the most highly ranked liberal arts schools in the country.

Yet Blaisdell would likely not be surprised. As he wrote to Scripps in 1923, “all I can hope to do is to draw the outlines of a project so fine and yet so sane that the generations will not suffer it to fail.”