Don Daglow ’74 has earned much acclaim and multiple awards—including an Emmy—for designing some of the earliest video games in a range of different genres, including arguably the world’s first role-playing game (RPG),✱ the first world-building game, and the first graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG).✱ Indeed, you can draw a straight line between many of his contributions and blockbuster games like “Roblox,”✱ “Grand Theft Auto”✱ and “Minecraft”✱ that help fuel an industry that rakes in nearly $200 billion in annual sales.

✱ Confused by all the acronyms? See glossary at the bottom of the page.

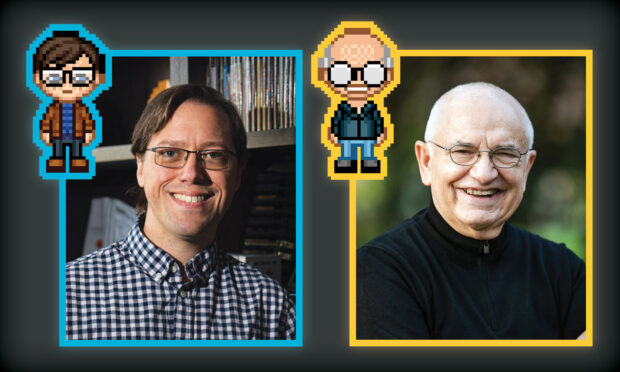

This spring Daglow jumps onto the SageCast podcast for a wide-ranging conversation with Pomona Associate Professor of Computer Science Joe Osborn, who—in addition to having an MFA in game design—conducts research on artificial intelligence and its impact on interactive systems like video games.

Osborn spoke with Daglow about some of the design pioneer’s favorite projects and how the medium has evolved to become a catalyst of creativity for hundreds of millions of people around the globe.

(Please note that this interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

![]() Osborn: Before you got to Pomona, what were some of the earliest experiences that felt “creative” for you?

Osborn: Before you got to Pomona, what were some of the earliest experiences that felt “creative” for you?

![]() Daglow: My original goal when I was in sixth or seventh grade was to be a writer, then a novelist, then a playwright. In high school I was writing plays and had some things performed, and was very much set on that goal, so when I came to Pomona I already had a vision of wanting to do something in theatre. As a sophomore I saw a really innovative production of “The Taming of the Shrew” that just made my head explode in terms of what theatre could be.

Daglow: My original goal when I was in sixth or seventh grade was to be a writer, then a novelist, then a playwright. In high school I was writing plays and had some things performed, and was very much set on that goal, so when I came to Pomona I already had a vision of wanting to do something in theatre. As a sophomore I saw a really innovative production of “The Taming of the Shrew” that just made my head explode in terms of what theatre could be.

Osborn: In the last couple of decades there’s been a bit of a moral panic around video games—some educators, parents and members of Congress believe that they stifle creativity and that kids spend too much time in front of the screen and can’t think or imagine things for themselves. How do you feel that video games can inspire creativity in yourself and others?

Daglow: There’s no question that games can inspire creativity in the same way that great writing can. When I was a kid I read Dr. Seuss books and then started writing my own, styled after [him]. I grew up in a family where I was very loved, but also where it got very loud and combative, so retiring away to books and games was part of my defense against the world. It’s a place you can go that can give you comfort and perspective, and open up great wide vistas.

Osborn: This makes me think about some of the specific sources of inspiration you’ve drawn from in your work, including “Dungeons and Dragons” (D&D)✱—also the subject of moral panic in the ’70s and ’80s. What inspired your interest and embarking on the project of making a “D&D” game while at Pomona?

Daglow: I started out making games by chance. At the time computers were really only accessible to faculty and upperclass students majoring in math and the sciences. But in 1971 [Math Professor] Paul Yale and Jim Cowart ’73 got a grant from the Sloan Foundation and put two computer terminals in the lobby of Mudd-Blaisdell. One morning I walked in and heard the terminals making a clickity-clack kind of sound, and [the folks there] said, “Oh, hi! Want to learn how to use the computer?” You could interact with and play games on it, which [I loved] as a theatre person.

So, before “D&D” came along, I’d been writing games—and plays—at Pomona for several years. For my senior play, Pomona theatre majors had other projects they were committed to, so I had actors join from “Strut and fret” at the other five colleges. Fast forward a year after we graduate, and these actors have fallen in love with this new “D&D” game, and I got a call one day to play. I go, and my brain just explodes [thinking about] all the things this could be. At that point, it wasn’t that I wanted to write the “Dungeon” game. It was that I couldn’t not write it.

Language—and expression—is how we as individuals take our emotional experiences and translate that into something that registers with someone else.”

-Don Daglow

Osborn: There’s a lot of energy right now around large language models✱ (LLMs), but they make content in a very different way from the interactive fiction✱ of the past. How do you feel that [LLMs] compare to the kind of stuff people were doing on computers in the 1980s?

Daglow: I’ve got a fair amount of experience with LLMs, and it’s really apples and oranges. When I was learning to program at Pomona, I actually wrote an early chatbot✱ called ECALA. I treated it like a game [of] trying to fool the player into thinking they’re talking to a real person—and what LLMs do is allow the computer to fool the player much longer than we could. Ask [an LLM] to write a 500-word story … and you can see the standard story-beats it’s trying to recreate. But it feels like it was written by a human being who’s way too self-important and trying too hard.

Compared to what we had 50 years ago, [AI today is] a hell of an accomplishment, and there are certain ways in which it’s been a useful tool that can save a lot of time for people. I think there have been some good examples of games that have been enhanced by AI: if it’s done selectively, you can get some very nice “non-playable character”✱ interactions that add more depth. The problem is business people start thinking that you can take that good idea being dropped into places selectively and start saying “what if I put it everywhere?” And that’s not really how it works. Ultimately the chemistry that goes into human creativity is different, but we should expect machine creativity to continue to improve.

Osborn: There’s always that tension of whether thought prefigures language or language prefigures thought. In the ’70s and ’80s the former paradigm was dominant, and now we’re in a world where it seems like many people

believe that a language machine also knows and understands things. It’s an

interesting debate.

Daglow: This makes me think of my playwrighting advisor Steve Young. He would always say that passion and emotion are what drive our lives and, therefore, our stories. Language and expression is how we as individuals take our emotional experiences and translate that into something that registers with someone else.

He would say, “Give somebody an idea, and maybe they’ll remember it until Monday, but make somebody feel an emotion, and they can’t help but remember it on Monday.” In fact, maybe they can’t stop thinking about it for weeks, months or even years. If you think about movies that hit you hard, or a book that changed how you look at things, that’s because the emotion was translated into language, which conveyed the power and the relevance to an individual. In 50-plus years of leading teams and producing video games of all kinds, that perspective has helped almost every single day of my career, which is why I feel such gratitude to Dr. Young. What a gift.

A brief history of consoles

* Years represent U.S. release dates

Atari 2600, 1977

As one of the first systems with interchangeable cartridges that let you play more than one game, made the medium viable for home use (Units sold: 30M+)

Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and Game Boy

Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), 1983

Alongside its 1991 sequel SuperNES, played a key role in kick-starting gaming, with its directional “D-pad” becoming widely adopted by other platforms (Units sold: 62M)

Nintendo Game Boy, 1989

Ushered in the birth of the portable gaming device (Units sold: 119M)

Sony PlayStation and PlayStation 2

Sony PlayStation, 1994

Introduced 3D graphics and CD-quality sound, as well as more narrative-driven titles (Units sold: 102M)

Sony PlayStation 2, 2000

Popularized the idea of consoles as entertainment hubs, with a DVD player and internet collectivity (Units sold: 160M)

Nintendo Wii and Switch

Nintendo Wii, 2006

Spearheaded the gesture-based interface, spurring further research in augmented reality and virtual reality (Units sold: 101M)

Nintendo Switch, 2017

Revolutionized the “hybrid console” both for portability and home systems (Units sold: 146M)

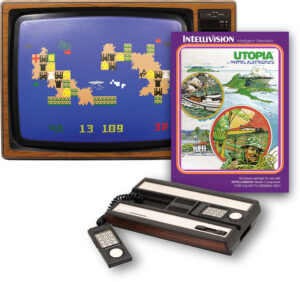

Roots of Utopia

Published eight years before “SimCity,” “Utopia” was developed for Mattel’s 1979 Intellivision console and later recognized by Guinness World Records as the first simulation video game.

Osborn: You can view “Utopia” as a “building” toy—as a way to make little worlds. Kids have played with building toys for millennia. Games like “Minecraft” have over 40 million monthly users who play seven-plus hours a week. (My own son is among them, and I think he’s pulling up the average.) What does this explosion of interest in world-building games✱ say to you about what people are interested in engaging with, and what do you know about how different people have used these games in different ways?

Daglow: It’s a great example of the power of video games, to take established kinds of toys and expand them. When I was a kid I played with my dad’s old Erector set, and then Kenner’s [Girder and Panel] building set, which was basically plastic pizzas that you could fit together to build buildings and bridges with. It’s that continuation of [the idea that] building things is fun.

Just this idea of “what if” is so fascinating: if I do this, what will happen? We face that in real life all the time. If I have the doughnuts for dinner, instead of something with protein and vitamins, what will happen? “Well, I have a good idea, so I think I should have the protein.” That’s a constructive part of our lives—and I think video games have just made that explode in wonderful ways.

Don’s deeds:

A brief timeline of Daglow’s most groundbreaking games

1976

Widely viewed as the first computer role-playing game (RPG) on non-classroom systems, “Dungeon” was based on the “Dungeons & Dragons” tabletop RPG that had launched in 1974. Developed in the tiny computer room in Daglow’s Mudd-Blaisdell dorm, it ran on PDP-10 mainframe computers and represented the first game with “line of sight” graphics pre-dating today’s first-person games.

1981

“Utopia” was a pivotal early sandbox game✱ where two players each control their own island. Arguably the first strategy game to incorporate real-time elements versus being exclusively turn-based,✱ it is often referred to as “Civilization 0.5”—a reference to the 1991 turn-based PC game that itself inspired influential games such as “SimCity” and “Minecraft.”

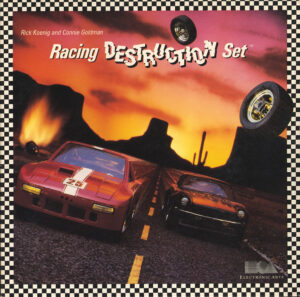

1984

1984

“Adventure Construction Set”* (with Stuart Smith) and its follow-up “Racing Destruction Set”* (1985, with Rick Koenig) represented a fundamental shift toward “game creation systems” in which users can develop their own games. It included seven small “toolkits” that enabled customized tile-sets, maps and objects to create different worlds, plus a complete original game by Smith called “Rivers of Light.”

1991

Another entry in Daglow’s “D&D”-related productions, “Neverwinter Nights” is widely considered the world’s first graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), spurring a devoted following of users battling monsters in a medieval city. Pre-dating popular games like 2004’s “World of Warcraft,” in 2008 it was honored with a technical Emmy for its innovation in advancing the field of MMORPGs.

Another entry in Daglow’s “D&D”-related productions, “Neverwinter Nights” is widely considered the world’s first graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), spurring a devoted following of users battling monsters in a medieval city. Pre-dating popular games like 2004’s “World of Warcraft,” in 2008 it was honored with a technical Emmy for its innovation in advancing the field of MMORPGs.

Osborn: There’s also a vein of world-building games where [users] are making the actual rules and encounters. When you were producing “Adventure Construction Set” and “Racing Destruction Set,” what led you to think that these would be interesting in the market, rather than just be tools for game developers?

Daglow: When I joined Electronic Arts (EA) in late 1983, I was teamed up with Stuart Smith, who EA had signed to do another mythological adventure game [“Rivers of Light”] that he had already created and that they had already signed off on. We were talking about his project, and he said that what he had really wanted to do was something like “Adventure Construction Set.” This was aligned with what I had in mind: going back to when I wrote “Dungeon” on the mainframe at CGU, I was thinking “how can we fill all this space [in a game] without having to author everything individually?”

I went back to EA CEO Trip Hawkins and said, “I want to change the game that you all approved.” I was naive and new in the process, coming from this big corporation Mattel to what was then this little startup (EA), I didn’t realize that when you do something like that, you might get the game uncreated. But we made our pitch [to EA] to let people build their own adventures. Stuart would do the adventure game he was planning to do, but he’d build it with this ‘construction set,’ and then we’d have another tutorial adventure that’ll show you all the other things you can do with the game.

Osborn: From a user-creativity perspective, do you have experiences of how people have played world-building games like “Neverwinter Nights” and “Utopia” that have surprised you—ways that players’ creativity has taken you off-guard?

Daglow: Yes! It happens enough that we have an industry term for that: emergent gameplay. People play with our games in ways we never ever could have imagined. I would say that “Neverwinter Nights” is not about writing a story, it’s about the set design. You’re creating a world in which other people can play, and people will think of things you never would have thought of.

[Even] the idea that they would form communities—there are still people today playing the [19]90s versions of “Neverwinter Nights” from AOL, in some cases with people who they’ve been playing with for 35 years. There are groups on social media that I can go visit where these people still get together. Through the community they’ve created a world that’s infinitely bigger and longer-lasting than anything I ever created. If you provide a grain of sand and it builds into something like that over time, it’s just incredibly inspiring.

It can be different ways to play, it can be communities built on top of games, it can be completely new games designed using the same old tools and ways you would never expect. It’s one of the wonderful parts of doing game design, to see amazing things [done] not by professional game designers, but by a high school kid in New Orleans, or a medical assistant in Dubuque. They will come up with these brilliant, creative, innovative twists. It’s just so much fun to see.

Gaming 101: A Glossary

Computing & Gaming Concepts

Chatbots simulate human conversation using preprogrammed responses to user input.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are a type of AI trained on huge amounts of text to generate natural language responses.

World-building games let players design and shape virtual environments or societies. Role-playing games (RPGs) involve players assuming different characters in fictional settings, while “massively multiplayer online” RPGs (MMORPGs) bring together huge numbers of gamers interacting online in the same persistent world, which continues to exist and evolve while players are offline.

Strategy games tend to focus on planning skills rather than instant action. The two main types are turn-based strategy (TBS) like “D&D,” where players take turns, and real-time strategy (RTS) like “Warcraft,” where everyone plays simultaneously.

Sandbox games like “GTA” and “Minecraft” generally lack standardized or predetermined goals, leading to a larger degree of creativity. They are often “open world,” lacking traditional levels and borders like walls or doors that limit them to a particular area of play.

Non-player characters (NPCs) like quest givers or shopkeepers are controlled by the computer.

Interactive fiction tools like script generators create written content or character interactions, allowing players to navigate a text-based story by making choices to shape the narrative.

Games & Franchises

“Dungeons & Dragons” (“D&D”): A tabletop game known for storytelling and character customization, that laid the foundation for modern RPGs.

“Grand Theft Auto” (“GTA”): A crime game franchise where players complete missions and explore its vast open world at their own pace.

“Minecraft”: A sandbox game where players build and explore block-based environments. Its open-ended gameplay has inspired countless user-created modifications and worlds.

“Roblox”: A platform where users create, share and play user-generated games. With millions of user-created experiences, it functions as both a game and a development platform.