After a long, slow slide that began in the era of petticoats and suffragettes, the American fertility rate recently reached a new nadir. In 2023 U.S. moms birthed 3.6 million babies—about 76,000 fewer than the year before and one of the lowest totals since 1979.

A University of Chicago professor,

Heffington ‘09 has written about motherhood and women’s movements for TIME, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.

It was a low-water mark that hinted at a bigger sea change. According to a 2024 Pew Research Center study, between 2018 and 2023 the share of adults under 50 who have no children and say they are unlikely to ever do so rose from 37 to (what else?) 47 percent. Fertility is falling in “basically every county: rich and poor, rural and urban,” says University of Chicago historian Peggy Heffington ’09, who studies contemporary and historical motherhood and reproduction. In 1970, the American fertility rate was about 2.5, above the replacement rate of 2. Today, it sits around 1.6.

Academics and parents themselves agree: this is a remarkably arduous moment to raise a child in the United States. But women opting not to have children is nothing new. In her book Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother, Heffington traces the history of non-motherhood from ancient Roman women who used lemons as ad-hoc diaphragms, through abstinent medieval nuns, and all the way to the present. “It felt important to me as a historian to establish that there is significant evidence of women limiting fertility for a very long time,” she says. “As long as people have been trying to have babies, they have been trying not to have babies.”

Still, many factors make parenting feel particularly difficult in 2025, including economic struggles, gender inequities, climate anxiety, mental health concerns and shifting expectations of community support. These accumulating challenges have been central to an increasingly common choice for young people of parenting age: not to parent at all.

Factor 1: Money talks

More than one-third of respondents to the 2024 Pew survey cited money concerns as a major reason for deciding against parenthood. The financial landscape for young people is tough, to say the least: a 2016 study from the Center for Household Financial Stability found that median millennial savings were 34 percent below what historic trends would predict; in a recent survey by the financial platform Step, more than one-third of Gen Z respondents reported running out of money every month.

Among the many costs of raising a new human, child care has emerged as especially exorbitant. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, American families pay upward of one-sixth of their median income on care for just one child—as much or more than what most pay for rent or mortgage. As tech entrepreneur Shadiah Sigala ’06 puts it, “You can see how with two or three children the calculus becomes absolutely untenable.”

On top of the cost of child care is its availability: over half of Americans live in “child care deserts,” with low-income rural and communities of color disproportionately impacted. This issue inspired Sigala to found Kinside, which provides a marketplace connecting families to caregivers in their area, helps companies build child care into their employee benefits, and works with local governments to improve larger care ecosystems.

But more accessible child care doesn’t help those who struggle to get pregnant in the first place. Fertility issues afflict many aspiring mothers, and while technologies like in-vitro fertilization (IVF) have opened up many new possibilities, they don’t come cheap, with a single round of IVF costing some $20,000. Heffington argues that, for some, such technologies actually “increase the pain of infertility in offering a promise where previously there was nothing you could do.”

Empathy Across Generations With Prof. Jessica Stern ‘12

By Lorraine Wu Harry ’97

This spring a child development paper from assistant professor Jessica Stern ’12 was selected by University of California at Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center as one of 2024’s “most provocative and influential findings on the science of a meaningful life.” We talked to Stern to learn more about her paper “Empathy across three generations.”

What is your study’s central research question?

Adolescents get a bad rap. The misconception goes something like this: Teens are self-focused, easily pressured to do bad things by their peers, and lacking mature social skills like empathy. But does the evidence bear this out?

Not really. In our observations, teens are deeply engaged in supporting others, particularly their friends, and peer interactions often encourage them to be prosocial. Our research team wanted to understand: How do teens learn empathy? How is empathy transmitted across generations? And what’s the role of teenage friendships?

How did you collect the data?

The KLIFF VIDA longitudinal study, led by the University of Virginia, began in 1998. We tracked 184 teens from age 13 into their mid-30s, and every year invited teens to the lab with their parents and closest friend, and recorded videos of their interactions. When teens were 13 we observed them talking to their moms about a problem they could use help on, and tracked how much empathy moms showed during that conversation. We looked for things like how emotionally engaged the mom was, whether she had an accurate understanding of the teen’s problem, and how much help and emotional support she provided.

Then, every year for seven years, we observed teens talking to their closest friend about a problem their friend needed help with. We looked for those same types of empathic behaviors in how the teen treated their friends. When some of those same teens were starting to have kids of their own about a decade later, we sent them surveys asking about their parenting behavior and their children’s empathy.

What were your key findings?

We found that teens who experienced more empathy from their mothers at age 13 were more likely to “pay it forward” by showing empathy for their friends in adolescence. For the teens who later had children, practicing empathy with close friends in late adolescence predicted more supportive parenting behavior a decade later. We were able to see how empathy is transmitted across three generations.

Our message is this: if we want to raise empathic teens, we need to give them firsthand experiences of receiving empathy from adults at home. More than lectures or pressure, teens need to feel what it’s like to be understood and supported. This gives them a model of empathy in action.

We also hope [to] give parents peace of mind, knowing that teens’ desire to hang out with friends is a boon for their social development (and perhaps their future success as caregivers). Supporting teens to cultivate close friendships may be important for them to hone their social skills by practicing caregiving for their friends.

Factor 2: Balancing the load

As she discusses the current state of non-parenthood, Heffington cites a Pew survey statistic she finds telling: 45 percent of women said they wanted kids in the future, compared to 57 percent of men. “What we’re seeing is not that women like babies less than they did,” she says. “It’s that they’re very aware of who’s going to be doing the work, whose career is going to take the hit, and who will do the vast majority of mental labor.”

LOW FERTILITY RATES

While the share of millennials who will never be parents is likely to climb to the highest in history, for now the generation with the lowest fertility rates in U.S. history is still those born between 1900 and 1910 who reached their childbearing years during the Great Depression. Amidst deep economic upheaval, a world war and a flu pandemic that killed millions, many women decided that now was not the time to create new life.

In fact, Heffington says that one-half to one-third of Depression-era pregnancies were aborted. “It’s only reasonable that people were looking around and thinking, ‘I can’t feed the kids I have; it doesn’t make sense to bring a child into this situation,’” she says.

That dynamic is familiar to Karen Magoon Pearson ’05, who adopted four children with her husband. As a couple, they seek to be egalitarian in their sharing of household chores, and mostly succeed. But, like many mothers, Magoon Pearson has been tasked with nearly all the intangibles: keeping track of the kids’ schedules and school workloads, planning outings, problem-solving and managing the logistics of a six-person family. “Emotional labor, the mental load; the code hasn’t fully been cracked there, even when both people want it to be,” she says.

Sigala, who now has two children, has also struggled in that arena. She experienced deep postpartum depression after her first child, exacerbated by a lack of support from her then-husband. “Mothers are the nucleus and the electrons; they’re keeping everything together,” she says. “They’re called to be many, many elements in the atom. And they’re just breaking.”

Although the twin concepts of mental load and emotional labor have finally entered the collective conversation, Heffington argues that that awareness is not enough to counter the deeply ingrained expectations that befall mothers. “Women have become more aware of the effect [parenting] will have on their lives, their marriages, their careers,” Heffington says, “and are increasingly thinking that it’s not a good trade-off.”

Factor 3: A hostile climate

The changing climate has also had profound effects on people’s parenting proclivities. In the 2024 Pew study, one in four respondents said their choice to not have children was primarily for “environmental reasons,” while 38 percent cited a slightly broader “state of the world.” (Cue meme of “gesturing broadly at everything.”)

These choices are not evenly distributed among young people, notes Jade Sasser ’97, an associate professor of gender and sexuality studies at University of California, Riverside. Surveys by the Yale Center for Climate Communications consistently find that people of color experience more emotional distress—and suffer from more clinically diagnosable mental health issues—due to climate change. Their fertility decisions are also more likely to reflect that experience. In a 2020 survey, 41 percent of Latino respondents and 30 percent of Black respondents cited climate change as a factor in why they did not have children, compared to 21 percent of white respondents.

This trend was compelling enough to inspire Sasser to write a book about it. Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question explores younger generations’ fear and grief around the climate emergency, the ways that people of color are disproportionately impacted, and the reproductive decisions that result.

One of Sasser’s more surprising findings was that young people are less fixated on the negative impacts their hypothetical children will have on the planet, than on the negative impacts the planet will have on their children. That is, in previous decades people who cited environmental factors in their fertility decisions were usually considering issues like overpopulation and pollution—how bringing a new human into the world would damage their surroundings. Now, the feeling is that the damage has been done, and the fears focus more on how the consequences will affect quality of life for a new generation.

Many people Sasser interviewed wanted children but felt that subjecting new humans to the potential horrors of climate change felt unethical. “If I had kids amidst a catastrophe like a hurricane, I would be worried every day,” one woman told Sasser. Would she be able to keep them safe?

MORE ‘HUMANE’

To Not Create

MORE HUMANS?

In 1969 Mills College valedictorian Stephanie Mills gave a speech eulogizing the children she felt ethically bound not to have: “I’m terribly saddened by the fact that the most humane thing for me to do is have no children at all,” she told onlookers.

In contrast to many of today’s parental-environmental concerns, women like Mills were concerned about the polluting impact and resource-intensiveness of new babies—the impact their children would have on the environment, rather than the impact the environment would have on their children.

The year before, author Paul Ehrlich had published The Population Bomb, predicting dire effects for a runaway population: pollution, starvation, widespread destruction. The book contributed to widespread anxiety among women like Mills, who felt the best choice they could make was to opt out of motherhood and not add to the problem.

Although climate anxiety and grief are common across race and socioeconomic strata, people of color experience them more strongly due to structural inequities, Sasser says. (In her book, she points to one potent example; a report analyzing FEMA records from 1999 to 2013, which found that 85 percent of post-disaster buyouts went to white families.) “Climate change seems to be a threat multiplier,” she explains, “meaning that the other reasons people have for either not wanting children or being ambivalent are compounded by emotional responses to climate change—and that’s worse for young people from marginalized communities.”

Factor 4: The parenting happiness gap

One hot take you won’t hear on Oprah: American parents seem to consistently report feeling less happy than people without children. (Specifically, 12.7 percent less happy, according to a 2016 meta-analysis of adults across 22 countries.) Heffington says that, in the U.S. at least, there is no kind of parent—new parents in the thick of it, empty nesters, step-parents—that is, on average, happier than people without children.

The so-called “happiness gap” is particularly acute for women, which Sigala and others attribute to the true emotional weight of motherhood and the opportunities young women give up by having children. Since full-time child care can often cost as much as a professional woman earns, Sigala says that women around her often feel the “pernicious, intractable” pressure to step away from work and care for their children or families. “You can see how it starts to pile up, and before you know it, women are hugely disadvantaged in their professional lives and their ability to have strength and freedom,” she says.

Still, data from Europe suggests that, while raising children is challenging everywhere, the kids themselves are not the problem. In a meta-analysis, researchers found that in countries such as France, Finland, Norway and Sweden, the gap disappears or is even reversed, with parents reporting that they are happier than non-parents by up to 8 percent. Their results showed that a few simple factors make this paradigm possible: vacation time, parental leave, sick leave, and affordable or free child care. “It doesn’t require massive infrastructure,” Heffington says. “Just dialing down some of the pressure American parents experience could make a huge difference.”

GET THEE TO A NUNNERY

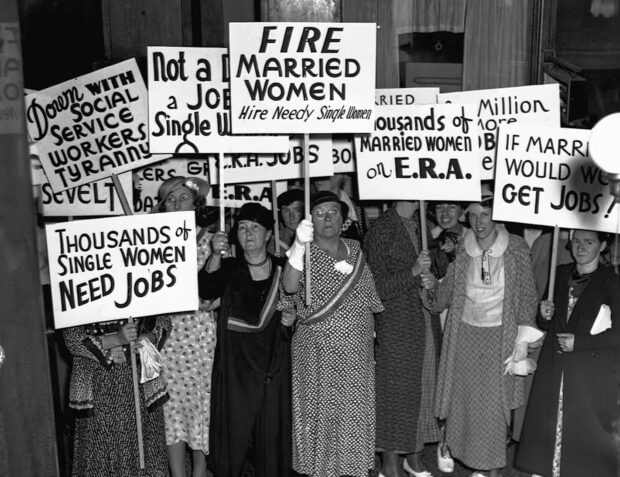

In 1869 Arabella Mansfield was the first woman to pass the bar to become a lawyer. This milestone was a sign of a larger trend: women gaining better access to education and entering the workforce in increasing numbers.

In response, starting around 1900, both private companies and government entities began instituting “marriage bars” that banned married women from the workplace. These bans, which stemmed in part from racist fears around a plunging white birth rate, were common in industries such as insurance, publishing and banking, but in some cases were implemented statewide. A 1935 Wisconsin resolution called working married women “a calling card for disintegration of family life.”

Heffington says that marriage bars were intended to force women to go back to domestic spaces after they got married, which is “often exactly what they did.” But a growing number chose instead to delay marriage or opt out of family life altogether—either to pursue their professional priorities or because they could not afford the economic costs of ceasing work.

Factor 5: Losing the village

In writing her history of non-parenthood, Heffington found that she was actually writing a story about the transformation of the American home, a transition “from something deeply embedded in community structures offering support to the isolated nuclear family.” Although the familiar single-biological-unit structure might seem inevitable from our perspective, work from Pomona professor emerita Helena Wall shows that alternative configurations were flourishing in North America as recently as 400 years ago. “Colonial Americans understood the family only in context of community, with women from throughout a community taking active part in raising children,” Heffington explains. “They spent their whole lives passing in and out of each other’s houses.”

But during the 19th century, a major demographic shift found young people flocking from rural to urban areas for factory jobs—away from those support systems and toward the smaller, suburbanized nuclear family so typical today. Heffington sees today’s millennial experience as an extension of that shift. “We’ve replaced community support structures with ones you have to pay for, with relatively predictable results in terms of fertility,” she says.

Indeed, the loss of the proverbial “village” it once took to raise a child is significantly impacting younger generations’ parental reluctance. For example, while a network of relatives and neighbors watched over Sigala during her childhood, as a young adult she lived in a succession of different cities, each time starting anew and alone. “When my friends have grandparents around to take the kids, even one day per week, I’m very envious,” she says. And babysitting neighbors? As extinct as the dinos and the dodos.

Magoon Pearson also struggled with a lack of support after her oldest child’s academic troubles led her to homeschooling; not long after, the pandemic found her at home teaching all four children. “By the end of that year, I just couldn’t do it anymore,’” she remembers. Continued changes to parenting norms only intensified the difficulty. During her own childhood, she often spent time independently at friends’ houses or birthday parties. “It wasn’t like parents were expected to be everywhere all the time, doing everything their kids were doing,” she says. “Now, you kind of are, so you never get a break.”

Missing Community

One of Heffington’s favorite historical examples of non-motherhood comes from French Colonial Canada. Birth records from the 16th and 17th centuries tell a powerful story about the importance of community support in parenting. Demographers studying the era noticed that the farther a woman moved from her mother, the fewer children she was likely to have—up to four fewer children if she lived more than 200 miles away. Those children were also more likely to die early in their lives, while children whose mothers stayed closer to home had better odds of surviving until adulthood.

Heffington sees this pattern as proof of how much impact a woman’s community had on her parenting capacity. “It’s not just about where her mother was but about the community, about how important support networks are for people having kids and for those kids being able to thrive.”

Next steps: should we (population) panic?

Since President Trump started his second term, his administration has taken a staunchly pronatalist approach. Vice President JD Vance has spoken disdainfully of “childless cat ladies” while Trump touts $5,000 “baby bonuses” for mothers-to-be.

Sasser interprets it all as part of a larger, politics-driven “population panic”—and one that she treats with a heavy dose of skepticism.

Indeed, while Magoon Pearson feels some anxiety when she considers a future with fewer children—what will happen to Social Security? Will there be enough young people to keep the gears of society moving?—she rejects the idea that the childfree are inherently selfish, citing family and friends who instead spend their time on other meaningful endeavors. With four children’s lives to manage, and so many places where the world needs help or healing, “I’m bogged down with this anxiety that I’m not doing enough, stuck at home,” she says. “Thank goodness there’s people out there with the time and energy I don’t have!”

Sasser, Heffington and others argue that any supposed population crisis is at best overblown, and at worst manufactured. While some East Asian countries are indeed seeing small towns depopulating and villages with no children, the U.S. has “the privilege of being a place where people want to come to raise their families,” Heffington says.

Zooming out, the larger context is that fertility rates tend to reliably settle under 2 across time and cultures as women get more access to education, contraception and professional opportunities.

Heffington suggests that policymakers could look to the European countries with happier parents for a model of how to make parenting healthier. France and Sweden, for example, have built infrastructures conducive to parenting that include paid and extended maternity leave, prenatal care, free child health care and subsidized daycare. “If you’re forcing women to choose—whether it’s because of professional ambition or economic survival—some are going to choose not to have kids,” Heffington says. “If you make it easier for them to have both, they’re going to have both.”

Alternative Paths

Although they might not have explained their choices in so many words, medieval nuns have their own unique role in the history of non-motherhood. Heffington says that medieval biographies of saints showed these women to be “very clear from a very young age that they do not want to be wives or mothers, and [that] the path they choose is the only other option available to them.”

At that time, girls from good families would have been married off in their teens or younger, with the expectation that they begin birthing heirs soon after. But the convent offered an alternative, respectable path, where teaching and serving God was just as valuable as marriage and family. Many engaged in scholarship and mentorship, and became advisors to kings or emperors.

Their biographies portray this as a valid choice to “spend their time doing other things,” Heffington says. “Some of these women built lives that were clearly very rewarding—and didn’t include motherhood.”