The numbers tell a sobering story. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for 10- to 24-year-olds—a hefty chunk of Gen Z— suicide is the second leading cause of death and has increased more than 50 percent since 2000. Across a range of psychological surveys Gen Z often is found to be the loneliest, most anxious, depressed and heavily medicated generation ever.

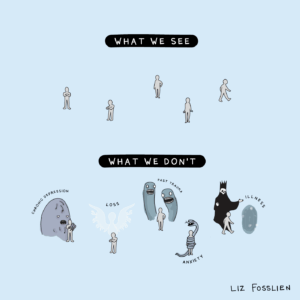

Many mental health professionals call it a crisis—but perhaps there is also a crisis of perception.

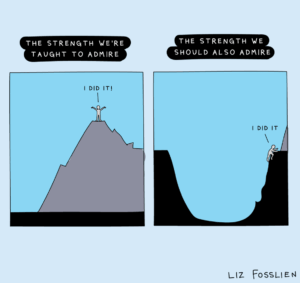

Gen Z folks—and, to some extent, their millennial elders—have often been slapped with disparaging labels like “the Anxious Generation,” “the Therapist Generation” or even “the Snowflake Generation.” While no one can contest the heartbreaking stats on suicide, loneliness and depression, another thing that can’t be dismissed is Gen Z’s ability to adapt to adversity. They report being sadder, but—based on conversations with several mental health professionals in the field—in many ways they are also braver.

We recently spoke to three experts on the topic:

- Pomona College Assistant Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students for Academic and Personal Success Tracy Arwari

- Crisis Systems Medical Director at King County, Washington Dr. Matthew L. Goldman ’08

- Licensed Clinical Social Worker and Clinical Director Jasmine Lamitte ’08 (below), author of The Black Mental Health Workbook: Break the Stigma, Find Space for Reflection, and Reclaim Self-Care

Today’s young adults have had more than their fair share of battle wounds. They were a key casualty of COVID-19, both in actual deaths—approximately 15 million worldwide—and in the wrap-around effects of the pandemic on their mental health. When some of your most formative years are spent communicating via screens, the consequences are sharply felt.

“Psychosocial development was basically stalled for a period of time for a lot of kids,” says Goldman. “The increased use of services, and increased suicidality among youth, suggests that COVID was absolutely a catalyst for worsening the youth mental health crisis.”

Jasmine Lamitte ’08, author of The Black Mental Health Workbook: Break the Stigma, Find Space for Reflection, and Reclaim Self-Care

Lamitte agrees, pointing specifically to something she noticed when schools reopened: Young people who had isolated at home had missed key developmental milestones, leading to behavioral challenges and a huge uptick in both social and generalized anxiety.

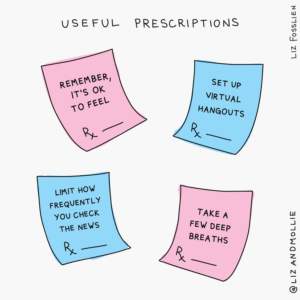

The social isolation may be exacerbated by increased digital connection. Social media and digital connectivity certainly have their benefits in increasing awareness of challenges that other young people might be going through.

Although Lamitte is encouraged by Gen Z’s growing comfort talking about mental health, she says that platforms such as TikTok have rampant misinformation that can lead users to self-diagnose and feel like they can handle things on their own without therapy.

Pomona College Assistant Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students for Academic and Personal Success Tracy Arwari

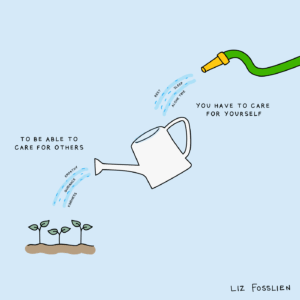

Arwari says that help-seeking behavior has become much more ubiquitous on campus in recent years, which she attributes to Pomona’s own proactive efforts toward outreach and prevention, as well as a larger societal trend toward being open around mental health and self-care.

“Ten or 15 years ago, you did your best to tread water on your own and you had to have quiet faith that this, too, would pass,” she says.

Experts see a greater willingness among Gen Z to seek therapy earlier and more consistently, versus waiting until things get intensely challenging.

“With my generation, the process started in college or after,” says Lamitte. “Now kids are coming out in high school and exploring trauma they’ve experienced, to not necessarily carry that burden by themselves.”

While some label Gen Z as “the Therapist Generation” with disdain, Goldman considers it a net positive that there’s been such a banishment of stigma, which translates to prioritization of funding for mental health services, not to mention greater receptivity to treatment and more engagement in the healing process.

Lamitte adds that younger generations are increasingly open to exploring different modalities that they may have first encountered on social media, including mindfulness meditation and “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.”

The experts argue that Gen Z has gotten increasingly comfortable being vulnerable about everything from anxiety to past trauma.

New Models of Care: What Systems Need to Catch Up

If the youth have caught up with the times, the systems unfortunately have not. Goldman says that the greatest barriers to care are the lack of services plus access. It’s a bind: there aren’t enough youth mental health services in general, much less ones that insurance will pay for. Complicating an already knotty situation is that pediatricians are often the ones prescribing medications for youth, without extra training in mental health or psychiatry.

“They’re doing their best and want to help, but often end up using the tools that they have at their disposal, like medications,” says Goldman. “There is plenty of data showing overprescription of psychiatric meds among kids.”

While many kids absolutely need the meds, data suggests widespread overprescription of antipsychotic medication that’s especially acute for children who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC), including boys who are involved in a juvenile justice or foster care system. Goldman says that this form of “diagnostic overshadowing”—in which BIPOC folks are more likely to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder or more serious mental illness—often can mask other diagnoses such as trauma or complex trauma.

Concern regarding mental health among youth in general is appropriately high. In King County, where Goldman serves as medical director for its crisis systems, there will soon be a 24-7 youth crisis facility with both urgent care and higher acuity units.

Given that dedicated behavioral health facilities tend to be much more effective at crisis care than in emergency departments or general hospitals, Goldman hopes that policymakers nationwide see the need to cover the gaps in care and support these crisis stabilization services. He cites Washington state’s requirement for commercial payment, which creates alternatives to sitting in an emergency room for hours or days waiting to be seen, or getting involved in a criminal legal system where people end up unnecessarily incarcerated.

Goldman says it’s also critical to have an outpatient system that can receive people in the aftermath of a crisis. Post-crisis follow-up resources tend to be quite limited. Someone may receive good care during the crisis, but then face a lot of post-discharge barriers to being able to access ongoing support to prevent future relapse.

“There’s a risk of them falling through the cracks again,” says Goldman.

To mitigate that risk, King County is investing in post-crisis follow-up services that are dedicated to the aftermath of a crisis, so that anyone who comes through the crisis centers has access to ongoing care. It’s based on one of the leading national models for youth crisis response, Mobile Response and Stabilization Services, or MRSS, a youth-specific model that comes from Connecticut; it is a field-based, community-based crisis response.

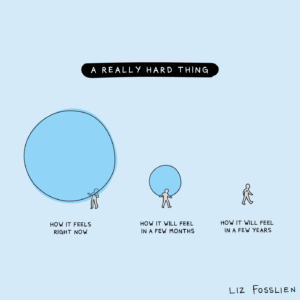

“Your anxiety or despair may sometimes be so overwhelming that you can’t see anything else. But it won’t be like that forever. There can still be lighter times ahead.” —Liz

If a young person or a parent calls into a crisis hotline like 988 or other local hotlines or a teen-specific hotline, and the call taker is concerned that the level of the crisis is more acute or severe than what can be handled on the phone, then they might dispatch a mobile response-type resource. While a lot of places have a general mobile crisis response that serves both adults and youth, the gold standard model is to have dedicated youth-specialized mobile teams, Goldman says.

“They’ll do the initial mobile response, but then they’ll also continue to support that child for six to eight to even up to 12 weeks after the initial mobile response,” he says. “And the idea is that it’s the team that does the initial mobile response that makes that initial bond with both the child and their family and then can continue to support them for that extended period.”

Sometimes that’s all that you need, Goldman says. Long-term outpatient or any other kind of community support isn’t always necessary because if it’s a crisis that’s related to something situational or circumstantial—bereavement, some event that happens—then youth can eventually do really well.

What Gives Us Hope

Gen Z’s crisis overwhelms, but there is hope rising nonetheless. For Lamitte, it’s their early pursuit of healing. For Goldman, it’s young people’s openness and receptivity. And for Arwari, it’s Gen Z’s commitment to kindness, camaraderie and advocacy.

“There is a lot in this world that can feel like doom and gloom at every turn,” she says. “But the thing that gives me hope is witnessing the way that students will hold each other up [and make] a rooted good faith effort to be kind to one another. The kids are all right.”

“It’s easy to equate success with visible achievements like a promotion or a new job. But it’s important to acknowledge and celebrate all growth, especially when it comes to mental health and well-being.” —Liz