The old career advice isn’t relevant anymore.

Start in the mailroom. Get your foot in the door. Grab a rung on the ladder and start climbing.

But what if there’s no actual office door, because your colleagues work remotely?

What if that mailroom is merely a metaphor in an age of electronic communications and AI-written emails?

Julianna Pillemer ’09, an assistant professor of management and organizations at NYU’s Stern School of Business

And as for the ladder, who among us actually still stays at one company for decades, waiting for a gold watch and a pension?

“It’s a totally different landscape,” says Julianna Pillemer ’09, an assistant professor of management and organizations at NYU’s Stern School of Business.

A New Generation of Workers

Young workers inhabit a changed work world, and they bring very different attitudes than previous generations. The last of the baby boomers who dominated workplace culture for decades turned 60 last year and are moving toward retirement. A decade ago millennials became the largest generation in the U.S. workforce, surpassing Gen X. Just two years ago, the boomers were eclipsed by Gen Z, those born from 1997 to 2010.

What do young workers want? Among the key values identified in a 2023 survey directed by Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business was that workers ages 24 to 35 prioritized flexibility and work-life balance.

That rings true to Hazel Raja, senior director of Pomona’s Career Development Office (CDO)—a Gen Xer who encouraged the office book club to read millennial author Lindsey Pollak’s The Remix: How to Lead and Succeed in the Multigenerational Workplace, so that the CDO team could better understand both the job seekers they counsel and their own colleagues.

The Remote Work Revolution

The pandemic ushered in the era of telecommuting, but many young people who experienced the isolation of the COVID shutdown have come to crave in-person collaboration, while also appreciating the versatility of hybrid work options.

“I think there’s this feeling of wanting the best of both worlds, to have days in the office where you can connect with the community but also the flexibility to say, ‘I’m working from home today,’” Raja says.

Even after return-to-work calls following the pandemic, remote work is entrenched in many organizations. Folks with bachelor’s degrees have benefited most: 52 percent of college graduates now work remotely some or all of the time, compared to 35 percent of the overall workforce.

Hybrid jobs offer potential gains for work-life balance. Yet NYU’s Pillemer—who earned a Ph.D. in organizational behavior from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and studies workplace relationships—says friendships can be key sources of motivation and support at work when managed effectively.

“I think this is often what leads to work feeling like a community, a place where you don’t have to hide who you are,” she says, noting her research on the concept of “strategic authenticity,” which involves finding the right balance between self-disclosure and professionalism at work. “I think there might be a disconnect between how little this younger generation is thinking these relationships matter and how much they actually do matter to their workplace happiness.”

Gen Z workers say they yearn for more in-person connection, but that it doesn’t have to be with colleagues. Now trending: meetup activities such as book clubs and hiking groups, and even platonic matchmaking apps like Bumble BFF.

Cohen ‘81 spoke in her TED talk about how to transition back into the workforce after career breaks.

Still, remote workers may miss out not only on networking and friendships but also on mentoring, says Carol Fishman Cohen ’81, a regular contributor to Harvard Business Review and co-founder and CEO of iRelaunch, a career re-entry company.

“To be in the office side-by-side with more seasoned professionals and have informal interactions with people is part of how you learn,” Cohen says. “You stop by someone’s office or walk out together from a meeting, and that’s where relationships are built and knowledge is transferred. If early-stage professionals don’t get to have that experience, it’s going to be much more difficult for them to learn what they need to know.”

Next-Gen Feelings

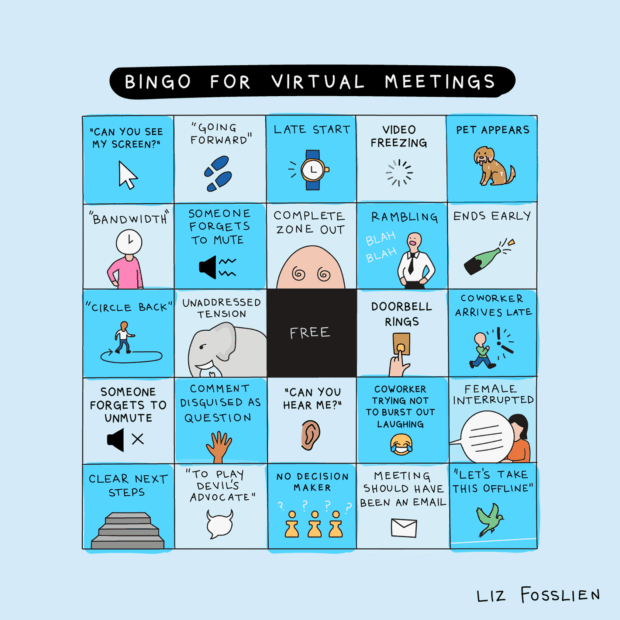

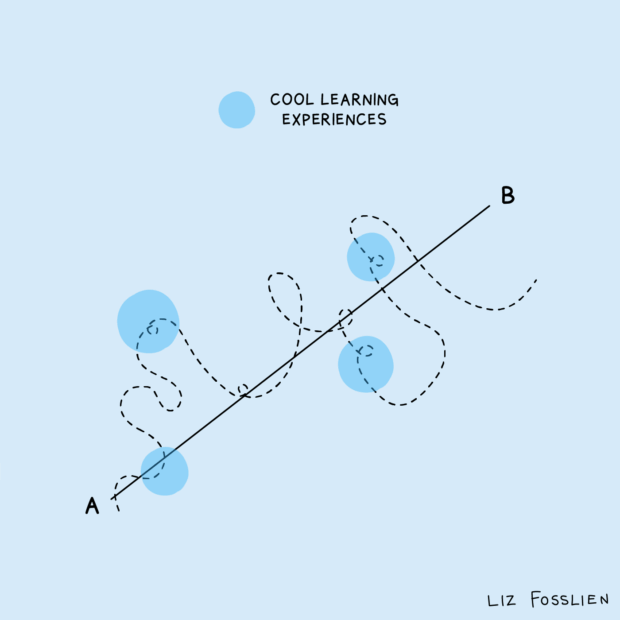

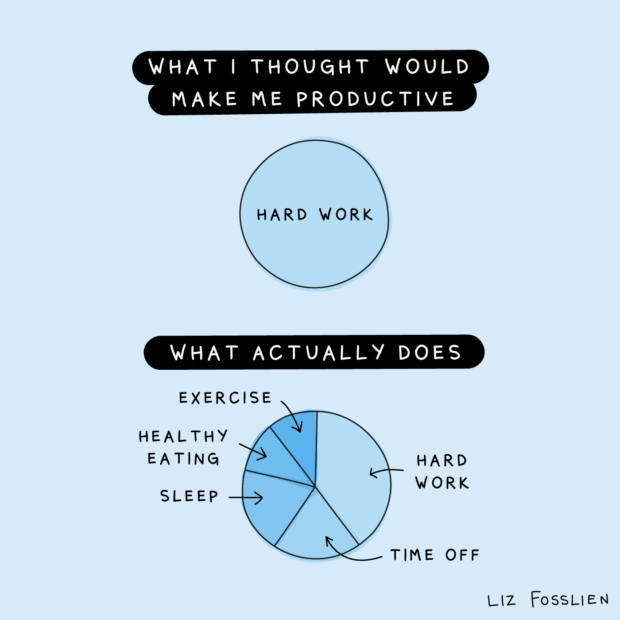

Liz Fosslien ’09 has spent nearly 20 years creating thoughtful, whimsical illustrations for publications such as The Economist, The New York Times and TIME. Often focusing on the topic of emotions as they apply to professional paths and workplace environments, she co-authored and illustrated the national best-seller Big Feelings and its follow-up No Hard Feelings, as well as helping illustrate Adam Grant’s New York Times bestseller Hidden Potential. Throughout this issue we’ll be featuring some of her illustrations that have resonated most strongly with younger generations, particularly those revolving around “the concept of giving yourself grace during hard times.”

- A popular strip that Fosslien says she couldn’t imagine creating pre-COVID

- Job-hopping: less linear, but sometimes more fruitful…

- Illustration by Liz Fosslien ’09

A Sense of Purpose

Work-life balance is no longer something people focus on only once they have kids and a household to run. Many Pomona students are thinking ahead, evaluating career choices by considering their personal priorities—sometimes choosing a city and then finding a job instead of finding a job and moving to that city—as well as by seeking more meaning in their work.

Raja says many students these days are often much more driven by things they’re passionate about, though she notes some students from less-advantaged backgrounds may still feel the need to maximize the financial return on their education.

“Generally, there’s not this aim for a ‘35 years of service’ pin,” she says. “More students are anchored by their values being met and doing work that is personally fulfilling.”

Nate Dailey ’23

Nate Dailey ’23, a high school senior when his family fled Paradise, California, in the early morning hours of the November 2018 “Camp Fire,” is one example of melding professional skills with personally meaningful work. He arrived on campus less than a year after his family’s home was one of nearly 19,000 structures destroyed in the deadliest wildfire in California history.

After majoring in computer science, Dailey embarked on a career in wildfire science as a research analyst for Deer Creek Resources, which helps communities and landowners prepare for wildfire. There he developed a computer model to detect overgrown parcels from roadside imagery that aids in both vegetation management and evacuation planning.

“I was really inspired to pursue something that was connected to the Camp Fire, and also my interest in computers and maps,” Dailey recently told Professor Char Miller in a Sagecast podcast. “Now I’ve been able to put it all together, and I think my Pomona education really helped me with that.”

Another key differentiator for the next generation of workers is that if a job isn’t right for whatever reason, today’s young people are not afraid to move on. While job-hopping once was a resume red flag, Raja and others say that applicants are now more likely to raise eyebrows if they stay too long, potentially suggesting that they don’t have other opportunities.

According to U.S. Labor Department statistics, in early 2024 the median time workers had been with current employers was only 3.9 years—the shortest tenure recorded since 2002. While the average job-stay for older workers was almost 10 years, for workers ages 25-34 it was a mere 2.7 years.

Camille Molas ’21, co-president of the New York City Alumni Chapter with her husband, Diego Vergara ’20, sees that phenomenon around her.

“A lot of people are on their third job already,” she says. “A friend of Diego’s already is on his fourth. Younger people are just more willing to say, ‘I’m out. This is not working for me.’” (See page 27 for more on Molas.)

Seeking Balance Beyond Wall Street

Camille Molas ’21 landed a coveted Wall Street investment banking job before she graduated from Pomona. The entry-level role with JPMorganChase paid her in the low six figures with the potential for five-figure bonuses and a big future.

Camille Molas ’21 landed a coveted Wall Street investment banking job before she graduated from Pomona. The entry-level role with JPMorganChase paid her in the low six figures with the potential for five-figure bonuses and a big future.

She left after only a year, jumping to Knowde, a startup focused on building software for the chemical industry.

The reason wasn’t only the famously grueling hours that Wall Street firms expect from young graduates.

“I was learning a lot and it was super interesting, but I felt like I was missing a certain something of actually building stuff,” says Molas, who completed the astrophysics track in the physics major at Pomona and spent her time with JPMorgan covering companies in industries such as aerospace, defense and chemicals. “These are already massive corporations that are no longer thinking about things like how you go from zero to one. I was really drawn to learning, ‘How do you even get things off the ground?’”

As part of the new Gen Z workforce, she also had expectations about balance, flexibility and personally meaningful work.

“I think what moved the needle for me to leave investment banking was that work-life balance,” she says. “It just kind of consumes your life.”

Working 80 or more hours a week is routine, and despite pledges by Wall Street firms to limit demands after the 2024 death of a junior investment banker at Bank of America who had been putting in 100-hour weeks, a Wall Street Journal investigation found some managers continued to pressure junior bankers to hide excessive hours.

“It’s not necessarily that you are working nonstop, [but] that you’re required to be ‘on’ all the time, which is almost worse,” Molas says. “It could be 14 hours one day, then eight, then 12 on the weekend. You’re not able to anticipate when you can be free.”

Don’t mistake her decision to leave Wall Street as a lack of ambition. Her ultimate goal:

“I would like to start a company.”

While working full time, she also has enrolled in a part-time remote master’s program in computer science at Georgia Tech to be able to better translate between the business and engineering sides of a company.

“I’m very big on understanding and being able to communicate, and think it’s important to know the language,” Molas says. “I want to make sure that I have at least the framework of where the tech people are coming from. There are always going to be the businesspeople and the engineers. You really need someone who can talk to both.”

Uncertain Outlook

While younger generations are being given more grace for job-hopping, their prospects aren’t uniformally positive. This year there were many headlines lamenting the job market for the Class of 2025 and, for the first time in decades, unemployment rates for college graduates under 27 have surpassed the overall average. Even the typically staid Economist chimed in with “Why Today’s Graduates Are Screwed.”

Factors include everything from federal spending cuts to the explosive rise of artificial intelligence, which experts say will affect entry-level jobs most because of more replicable tasks such as coding, number-crunching and summary writing. Despite that, Raja says she has seen such admirable adaptability for Sagehen job seekers.

“While it’s nice to be able to get a job at Amazon or Apple or Google, I think students like ours are versatile enough to say, ‘Well, I have these tech skills I could apply to another industry,’” she says. “‘Maybe a lot of the values I have are still being met because I’m not only working in an area that I’m actually interested in, but I’m making the same salary or I’m still building my network.’”

Ultimately, it may be the massive uncertainty in academia brought on by new federal policies that will have the largest impact on Pomona alumni, considering that one in four respondents from Pomona’s Class of 2024 First Destinations Report said they were headed straight to graduate school. In addition, many alumni who enter the workforce right out of college pursue a graduate degree within five years, Raja says.

Federal research grant cuts and wrangling over student visas and policies such as DEI mean some jobs and graduate school opportunities that used to be stable have evaporated, particularly in STEM fields and for international alumni. Proposals to limit federal loans for graduate students could also have a chilling effect, particularly on those seeking expensive medical degrees.

The impact on academia is likely to be felt by more than just graduate students: In Pomona’s 2023 Alumni and Family Attitude Survey, higher education was the number one job sector reported by alumni, ahead of science and medicine (36 vs. 27 percent).

Pillemer says most of her undergraduate business students at NYU remain focused on finance, consulting and tech, though they also are keenly aware of the potential to pursue more independent career paths such as internet content creation, entrepreneurship and gig work.

“As a scholar I’m reckoning with things like how we think about work and how organizations are structured, especially in a future when ‘employees’ could be bots and people are striking out on their own as entrepreneurs or influencers,” Pillemer says. “As students grapple with an uncertain job market and these sweeping changes in the way we work, they’re asking themselves, ‘What do I value?’ ‘What’s meaningful to me?’ And ‘How am I going to get paid to do it?’”