Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”

Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”

That attack line echoed from start to finish during the high-stakes federal trial in Maryland between two rival companies in the cutting-edge field of genetic engineering. The dismissive salvo was fired in the opening statement by the attorney for Cellectis, a large French firm that filed suit for patent infringement against its smaller U.S. competitor, Precision BioSciences, which had hired Seligman for its defense.

Seligman was more than just an expert witness. His research at Pomona had become a cornerstone for the case. Both sides cited Seligman’s work as a basis for the science on which their businesses had been built. Ironically, the plaintiff then found itself in the awkward position of having to undermine the validity of his work. It did so by claiming he had not actually produced anything concrete in his college lab that would invalidate the firm’s far-reaching claims.

“I don’t hold that against him,” said the counselor. “This is very complicated technology. It does not surprise me that he wasn’t able to do it. What does bother me is Precision attempting to rescue his (work) from the ash heap of failure.”

Seligman left court that day thinking, “Ouch! Did he really say that?” When cross-examined by that same lawyer, Paul Richter, Seligman found an opportunity to sneak in a mild retort, saying on the stand, “That was not very nice.” Considering the attack still in store, the lawyer might have mused, “If you thought that was bad, wait until you hear my summation.”

In those final arguments, though, Seligman’s side fired back with outrage and eloquence. Following a week of mind-numbing technical testimony, David Bassett, an attorney for Precision, rebutted the now infamous line. The court reporter transcribed the original reference as “ashes of failure,” but Seligman and others clearly remember it as a heap, and that’s the phrase that stuck.

To say Seligman’s work belonged in the “ash heap of failure” was “as incorrect as it is offensive,” said Bassett. “To the contrary, Professor Seligman’s article represented a monumental success from a small lab at Pomona College where (he) does his research with undergraduate students, 18 to 22-year-olds. And it paved the way for companies like Cellectis and Precision to do their work. … The real difference is that Professor Seligman was teaching the world what he had done and hoping that others would follow his blueprint.”

In the end, Precision won the infringement case and Seligman’s work was vindicated. The attack strategy against the likeable professor’s little-lab-that-could appeared to have backfired.

“I think that statement bit them in the ass,” he said. “Because even the jury kind of cringed when the lawyer said it. I mean, that’s really aggressive. And then when they got to know the witness—what a sympathetic guy I am—it was like, why would you do that? You could have made the point without going for the jugular like that.”

Indeed, it may have been the professor’s disarming, down home charm that won the day, as much as all the technical testimony about the DNA and microscopic structures called meganucleases. Beneath the complex science ran a compelling narrative that must have appealed to the federal jury empaneled in the district court of Delaware.

It was, in the end, a classic American underdog story.

The synopsis: Powerful and imperious European firm with raft of lawyers and battery of full-time scientists is defeated by scrappy U.S. start-up and its folksy professor with his one-man lab and part-time student assistants.

Seligman relished the role. In a PowerPoint presentation of the case presented recently to campus groups, he portrays the litigants as Team France v. Team USA. He uses slides to illustrate the uneven competition between the two companies and their dueling expert witnesses. For Cellectis, we see the flattering portrait of an award-winning genetics researcher from a big university. For the other side, we have Lenny Seligman, but the slide shows a picture of Homer Simpson.

The visual gets a big laugh.

A year after the verdict, Seligman still expresses astonishment when recalling the whirlwind experience of being a central figure in an intense international dispute about science. Interviewed in his office at Seaver Hall, where he presides as Biology Department chair, he also reflected on the awesome amounts of money circulating in science today, and what it means for those trying to teach and do research at a small, liberal arts college like Pomona.

“Part of me is happy with how things turned out,” he says. “At one level, it would have been great to be able to continue working on the I-CreI project without competition. However, we would never, at Pomona College, in my lab, have gotten to the point these two companies got to in five years. They were putting products out there, they were making enzymes that cut specific DNA sequences. It would’ve taken us so long to get there. So in the big picture, this is great. These companies are doing it, and they’re still graciously referencing our early work. It’s all good.

“We just have to find something new to do.”

Court and Class

Watching Seligman’s PowerPoint presentation about the case, posted online, gives viewers a flavor of his teaching style. He is engaging, enthusiastic and funny in a self-deprecating way. He’s also informal, standing casually at a podium with his shirttail hanging out and joking about wearing a suit only for court. But most importantly, he has a knack for explaining complex concepts to scientific novices, like college freshmen—or jurors.

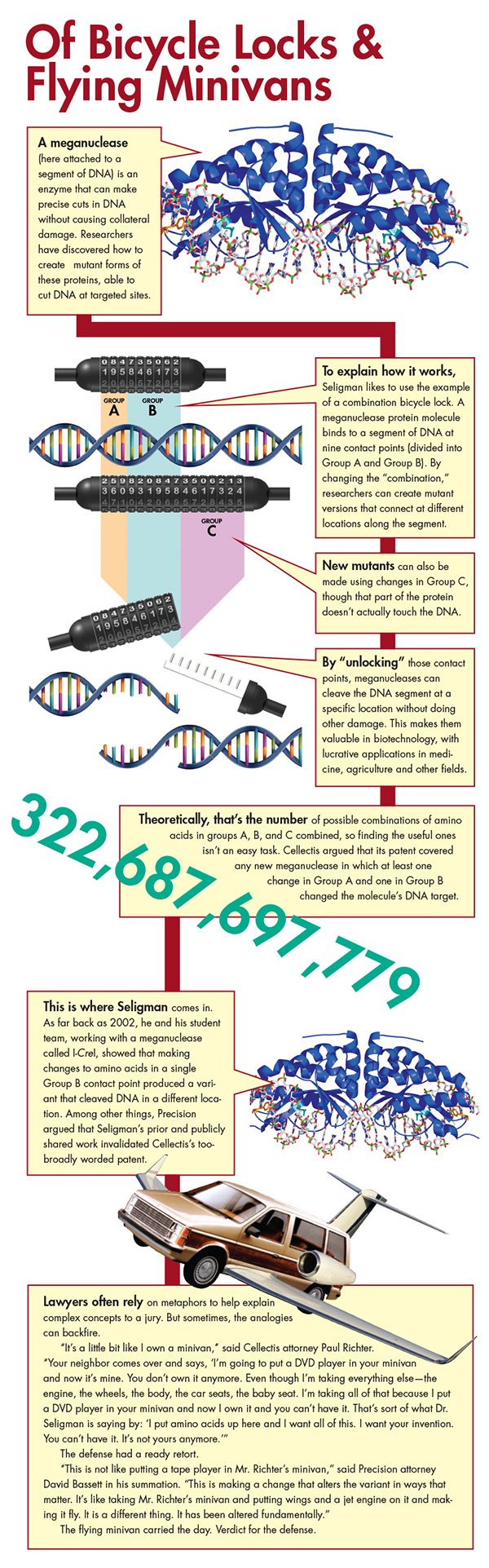

The concepts in this case involved the business of protein engineering using meganucleases, which have been described as “extremely precise DNA scissors.” Scientists have developed ways to alter these naturally occurring enzymes and make them cut DNA segments at specific, targeted locations, with potentially lucrative uses in medicine and agriculture.

“Court is interesting because it’s kind of like a class,” Seligman says. “But it’s not like a class at Pomona where someone’s going to raise their hand and ask a question and stop you. When I’m in a class and I’m lecturing off-the-cuff and I can see that I’m losing students, I’ll stop and I’ll ask them certain questions. You can’t do that when you’re an expert witness, but you can still kind of get the visual cues. You still could get a sense that (the jurors) were with you, and I really felt that they were. They weren’t glazing over.”

Neither were the lawyers. They were ready to pounce on every word, eager to point out the smallest inconsistency or weakness. And Seligman was trying to make sure he didn’t slip up.

So there was no Homer Simpson on the witness stand. In court, Seligman’s easy-going, spontaneous classroom persona was restrained. The transcript of his testimony shows a witness who is cautious, serious and coldly factual. By then, he had been through hours of grueling depositions, and he knew the name of the game—Gotcha!

“Well, the whole idea (of pre-trial depositions) is for them to get a sound bite that they can use in trial,” he says. “So they ask questions really quickly. The thing that was hard, especially for someone who’s not a lawyer, is that they move from one aspect of the case to another, rapid-fire. …Your mind is over here and they’re trying to get you to slip up, so they can say to the jury, “But didn’t you testify that…?”

Seligman pounds on his office desk to impersonate an intimidating attorney.

“I felt really guarded. In class, when I get a question and don’t know the answer, the first thing I say is, ‘I don’t know.’ And so that’s my default mechanism, because I’ll figure it out, and we’ll talk about it next lecture. But if you’re getting deposed, you can’t fall back on that answer because lawyers will shoot back, ‘You don’t know? Well, on page 285 of your third report, didn’t you write this?’” Here, his tone mocks a Perry Mason moment. “So you feel you have to be on your toes all the time, and really be thinking about everything you’ve ever written.”

At times, the legal wrangling was so contentious, even the judge sounded exasperated. During one testy confrontation, U.S. District Court Judge Sue L. Robinson threatened to give the lawyers “a time out,” like an angry parent with misbehaving kids.

Underneath, Seligman perceived a bitter dislike between the two companies. It was like a battle to the death. He speculates that Cellectis’s strategy was to put Precision, the much smaller firm, out of business, bankrupted by legal fees. So Precision could win the battle and still lose the war.

Call it the ashes of success.

“Cynically, a lot of us (supporting the U.S. company) thought this was all about trying to bleed them.”

Money and Science

The experience was not all cutthroat and high anxiety, however. Seligman also recalls the excitement of being swept up into the high-flying world of international business and high-priced corporate lawyers. He describes it with the wide-eyed wonder of a kid who grew up in Claremont and still uses the nickname he was given in kindergarten, rather than his full name, Maurice Leonard Seligman.

To Lenny, it was a thrill just being in New York for the deposition and looking out onto that breathtaking Manhattan skyline. He often punctuates his story with youthful expressions, like “awesome” and “oh, my gosh!” He breathlessly describes the “war room” where a battalion of lawyers in a suite of offices prepared for testimony. (“Oh, my gosh!”) And he recalls how lawyers worked through the night preparing challenges even to illustrations planned for court the next day, putting pressure on a graphics guy to create instant substitutions. (“Oh, my gosh!”)

“And you mix that with all this adrenaline and dread of being deposed—it was really exciting,” he says.

When it came to how much the defense paid him, the response might also be, “Oh, my gosh!” That pesky attorney made a point of making him divulge the fee in court: $400 an hour. “It was more money than I had ever made in a short amount of time,” he recalled in the interview. “It was a lot of money for me.”

The amount of money these companies dumped on this lawsuit raises larger concerns about the corrupting influence of big profits on basic research.

“The whole privatization of science is something that’s certainly to be looked at carefully,” agrees Seligman. “Did I ever think to put a patent out? I’m glad I didn’t, in retrospect. If somebody wanted to choke me like they tried to choke Precision, they would serve me and I would say uncle. There’s just no way I would have the resources to fight. But beyond that, there’s just something that’s really special about open science, where everyone is sharing everything and building on each other. And once it gets into the industry, it’s not open science. They’re protecting it. They’re hiding it until they get the patent issued.”

Bringing it all back home, Seligman sees implications for his future work at a small college. How can his little research lab compete with wealthy companies, often with ties to large universities.

“That’s what we worry about all the time in a place like Pomona College,” Seligman says. “You want to do interesting science, but it’s got to be small enough that you’re not doing the same thing that the big labs are doing because we don’t have the same resources.”

Focus on Students

Beyond doing good science, Seligman and his colleagues at liberal arts colleges have another mission to worry about—teaching undergraduates. In his own lab, he notes, research must also be a teaching tool, a training ground for future scientists. In this regard, he says, Pomona is in a perfect position to compete.

The work on meganucleases is a prime example. In the early days, before big money entered the fray, much of the research was being done by students at Lenny’s lab. Today, they all have their names—as full-fledged co-authors—on those important research papers that figured so prominently in the trial.

These were not graduate students or post-docs. They were undergraduates like Karen Chisholm ’01, Adeline Veillet ’03, Sam Edwards ’99 and Jeremiah Savage ’98, who co-authored Seligman’s pioneering 2002 paper, marking the first time researchers described making mutations in a meganuclease, called I-Cre1, that altered the site where it cleaved DNA. Two years later, Steve Fauce ’02, Anna Bruett ’04 and Alex Engel ’01 co-authored another of Seligman’s key research papers, along with Dr. Ray Monnat of the University of Washington, where Seligman got his Ph.D. and did his first work on meganucleases as a post-doc in Monnat’s lab. Finally in 2006, five other Pomona undergrads—Laura Rosen ’08, Selma Masri ’02, Holly A. Morrison ’04, Brendan Springstubb ’05 and Mike Brown ’07—co-authored a third paper in which new mutant meganucleases were described.

Many former students praise Seligman as a great mentor who inspired them to pursue science in graduate school. At least 10 of these 12 student co-authors went on to get doctorates in biological sciences or M.D.’s.

“He really fostered a good environment for learning and being productive,” recalls Morrison, who got her Ph.D. from UC Berkeley in molecular and cell biology. “He had several students in there at any one time, and everybody was really good about helping each other. It was not at all cutthroat competition. It was very much a supportive team mentality and there was also a camaraderie about it.”

Today, Seligman speaks about his former students as if they were his kids. He makes a point of mentioning them in his PowerPoint presentation, and even notes who got married and who just had a baby.

“We are so lucky to be a place that gets such great students,” he says. “It’s our job to work with them, to get them excited about science and keep them excited about it. I have no doubt they’re going to do really amazing things.

“And I’m going to sit back and smile.”