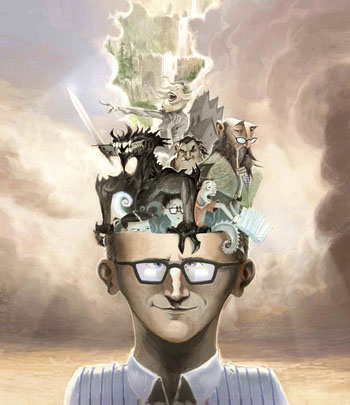

John Stephens ’94 grew up reading fantasy literature, devouring both the classics such as J.R.R.Tolkien’s The Hobbit and just about any well-worn, paperback sci-fi novel he could find. He read them all and dreamed of writing one of his own someday. So when Stephens decided to delve into the genre, pulling double-duty with his daytime job as a television writer, he knew the tropes of fantasy literature better than most. And he was determined both to tweak them and bring his own voice to The Emerald Atlas, the first novel in what will eventually become a children’s fantasy trilogy.

“Of course, tweaking those tropes is easier said than done,” Stephens says, laughing. “But you have to address that from the outset, particularly with the fantasy genre, because fantasy stories come from fairy tales and we all know the tropes of fairy tales—the evil queen, the damsel in distress—so well. Everyone grew up reading them and watching them in Disney movies, so they’re square in your mind the minute you start reading fantasy literature.”

Given the reception that has greeted Atlas since its April release, Stephens seems to have succeeded in contributing his own witty, modern sensibility to the genre. The Wall Street Journal praised the book, writing that a “great story is all in the telling, and in The Emerald Atlas the telling is superb.” The School Library Journal gave it a starred review, saying, “Echoes of other popular fantasy series, from Harry Potter to the Narnia books, are easily found, but debut author Stephens has created a new and appealing read that will leave readers looking forward to the next volumes in this projected trilogy.”

Atlas tells the tale of three children—14-year-old Kate, 12-year-old Michael and 11-year-old Emma—who discover an odd blank book which magically transports them back 15 years in time, plopping them in the middle of a battle royale between a beautiful, evil witch and a kind wizard. The children soon grasp that they have the power to change the course of history and find out the truth behind the sudden disappearance of their parents.

“I really tried to get to a different level of emotional reality for the three main kids,” Stephens says. “If you read the Narnia books, the emotions of the kids are really flat. It’s not like the Pevensie children are all that fleshed out, at least not in the way we expect today. You don’t get inside their emotions or how they really feel. Kids reading today want to really identify with children’s characters and you do that through the specificity of their emotions. That’s what I thought I could bring to the table.”

Stephens’ love for the otherworldly predates the decade he spent writing and producing television shows like Gilmore Girls, The O.C. and Gossip Girl, springing from the evenings when his father read The Hobbit to him as a young boy. During a leisurely conversation on the front porch of his American Craftsman home in Hollywood’s Beachwood Canyon community, Stephens recalls later re-reading the book on his own when he was 12, calling it a formative experience that shaped the rest of his creative life.

“Tolkien creates the kind of reading experience I like, one that takes you on a grand adventure into another world,” Stephens says. It’s mid-afternoon and 39-year-old Stephens, trim and boyish, his face framed by rectangular glasses, is enjoying a cup of fresh-brewed coffee, something of a necessity for a man who typically begins his work day at 4:30 in the morning. His wife, Arianne Groth ’94, and 13-week-old son, Dashiell, are napping inside.

After graduating from Pomona, Stephens spent a year abroad and then went home to Virginia, earning his M.F.A. from the University of Virginia. But what he learned at graduate school didn’t mesh particularly well with his natural skill set. “Nothing will teach you not to want to write fiction like getting your M.F.A.,” Stephens jokes. Translation: His interest in writing grand adventure stories ran contrary to his program’s emphasis on focusing on life’s small epiphanies.

Shortly after graduating, as he was watching the NBC hit medical drama ER on television one night, Stephens thought, “You know … somebody writes this stuff.” And with just that one thought in his head (and a lifelong love for movies and TV), he packed the car and moved to Los Angeles. Stephens’ one contact in town set him up with a manager, and he spent a year and a half writing coverage—that is, assessing and grading scripts—and doing a bit of journalism. Stephens then wrote a couple of spec scripts, which landed him an agent and a meeting with Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino.

“She asked me to tell her about my favorite shows and I spent the next 45 minutes talking about Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” Stephens recalls. “I walked out of there thinking, ‘Well, that was a disaster.’” Nope. Stephens wrote for the well-regarded comedy-drama for four seasons before moving over to The O.C. Around the time he changed jobs, Stephens read The Golden Compass, the first novel in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. Getting caught up in this great fantasy-adventure reawakened his desire to create one of his own. “It was like that Proustian moment: ‘Oh yeah, this is it. This is the thing I like doing,’” Stephens says.

Stephens spent four years writing The Emerald Atlas in the early morning hours before leaving for his television day job. “John has a deep love of writing,” Stephens’ friend and Gossip Girl co-creator Stephanie Savage says. “It’s what he does. So for him to write in different forms—for different audiences—only makes sense. It wouldn’t surprise me if he wrote a Broadway musical, a true crime thriller or an epic poem someday.”

But his choice of children’s fantasy was fortunate, since the genre is still booming, even in the post-Harry Potter era. In 2010, a year before the book’s publication, Publisher’s Weekly reported that Atlas created “the biggest buzz” at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, the annual international event at which rights to children’s books are sold. (In Stephens’ case, there was such strong interest that Knopf had snapped up the rights to the trilogy in an auction just before the fair was held.) PW also noted that the book got a big promotional push, including movie theatre advertising, and Atlas landed on The New York Times children’s bestsellers list in the spring.

Bookstore owner Maureen Palacios “fell in love” with Atlas after getting an advance copy, and she recalls later reading the first two or three pages to a group of elementary school students visiting her Once Upon A Time bookshop in Montrose, Calif. When she shut the book, “you could hear a pin drop,” she says. And later “their parents were calling begging me for the book. We sold out that day.”

So Stephens has an audience—and two more books to finish. He’s been working full-time for the past year on the second book, which is set to be published mid-2012. “The first book, you write for yourself,” says Michelle Frey, Stephens’ editor at Knopf. “Now you’ve got a bunch of people waiting for the next one. It’s a big difference.”

And, at times, Stephens says, a pretty big struggle. Before writing The Emerald Atlas, Stephens sketched an outline for the entire trilogy. He marked the big signposts, but he didn’t want to fill in too many details, fearing that too much planning would result in flat, programmed writing. “You read books that feel too outlined,” Stephens says, “books that read like screenplays. I wanted to know where I was going, but I like the journey to be part of it, too.”

However, Stephens found that as that journey progresses through three books, it becomes more about “getting the math right” and less about the thrill of discovering the characters. “With the second book especially, I’m conscious of what’s happening in the third book and not wanting to paint myself into a corner,” he says. “I have to make things happen where I’m not up against the eight ball in the third one and have to fight my way out.”

When he finishes writing the third book next year, Stephens would like to return to his old job, believing there’s a “great, balanced career out there,” one in which he could both develop television projects and write novels. “I’m not temperamentally suited to spend the next 15 years by myself in a room,” Stephens says. “At a certain point, you can take a year off a show business career fairly easily. People figure, ‘Oh, a creative hiatus.’ You take two or three years off and people wonder if you’re in a Tibetan monastery or a really intense rehab program. So, yes, it’s a big commitment. You hope the books work out and, if they don’t, that the career is still there when you get back.”

SIDEBAR: Time travel in Theory and Practice

After John Stephens ’94 finished the first draft of The Emerald Atlas, he handed it to his agent, who immediately asked: “So what theory of time travel are you using?” Stephens’ reply: “Well … uh … the one I’m making up.”

That answer didn’t pass muster, so Stephens began to research the different time travel theories frequently used in fiction. He found three common models. In multiverse time travel, featured recently in the mind-bending, sci-fi TV show Heroes, those going back and changing the past create a new branch of time.

At the other end of the spectrum is what’s called the predestination paradox, where a time traveler’s action in the past can wind up causing the historical event they’re investigating. J.K. Rowling employed that method in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, the third novel in her blockbuster series.

And then there’s the theory that Stephens wound up using in The Emerald Atlas, the idea of a single, changeable time stream that ripples and shifts every instance a time traveler visits the past. Example: Marty McFly goes back in time and alters the circumstances surrounding his parents’ first kiss in Back to the Future, and, when he returns to the present, mom and dad are well-adjusted and successful.

“That model is the most fun,” Stephens says. “You can watch things change. And you get to feel like you’re in on a big cosmic joke. Like I remember watching the end of Back to the Future where Michael J. Fox plays guitar at the prom, thinking, ‘Yeah, I know who Chuck Berry is.’”

But while mutable timelines might be the most fun, they’re also the most demanding on writers because of all the rippling changes. Since Stephens has always been the kind of reader who looked to see if writers were obeying the rules of the worlds they created, he was scrupulous to make sure his constructs held up, keeping elaborate flow charts on the wall of his office while writing Atlas.

“He was extremely meticulous about the time-travel elements of the story,” says Michelle Frey, Stephens’ editor at Knopf. “I couldn’t poke a hole in anything and, believe me, I tried.”